Hepatitis A and B vaccination is back in the spotlight as public health officials warn that outbreaks and chronic infections continue to hit communities with the least access to preventive care. After years of declining hepatitis A cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that widespread person-to-person outbreaks peaked in 2019, driven largely by transmission among people who use drugs and people experiencing homelessness. Thousands were hospitalized and hundreds died between 2016 and 2020, underscoring how quickly the virus can spread when vaccination coverage is low.

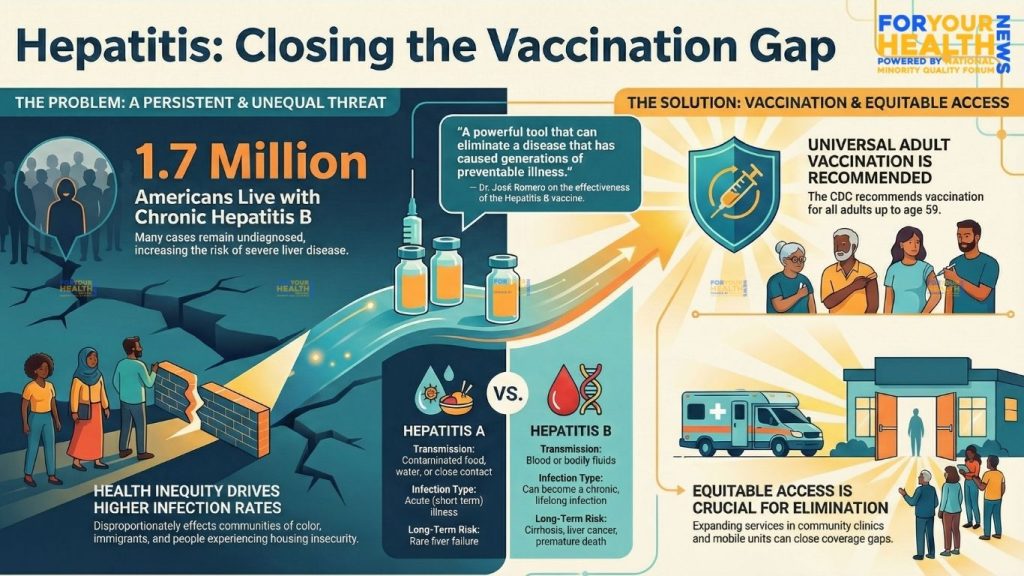

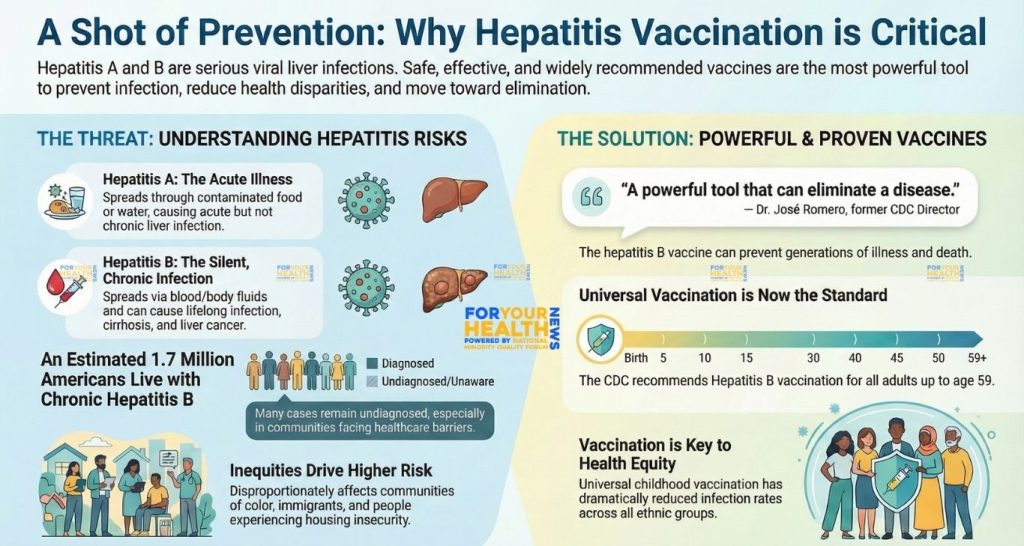

At the same time, hepatitis B remains a persistent, largely silent epidemic. A recent modeling analysis estimates that about 1.7 million people in the United States are living with chronic hepatitis B infection, with many unaware of their status. Hepatitis B Foundation CDC surveillance data show that in 2022 alone, states reported more than 16,000 new cases of chronic hepatitis B and nearly 1,800 related deaths. Because early infection often has few or no symptoms, people can live for years without a diagnosis while the virus slowly damages the liver.

The burden of these infections is not evenly shared. Federal data show that Asian Americans make up about 6 percent of the U.S. population but account for an estimated 58 percent of Americans living with chronic hepatitis B, reflecting higher prevalence in many countries in Asia and the Pacific where many immigrants were born. Black, Latino, Native, and immigrant communities also face higher risks linked to structural factors such as lack of insurance, language barriers, limited access to primary care, and discrimination in the health system. For people experiencing homelessness, unstable housing, crowded shelters, and limited access to sanitation make both hepatitis A and B more likely.

Understanding the risks – and the protection vaccines offer

Hepatitis A and hepatitis B are both viral infections that attack the liver, but they spread in different ways and have very different long-term consequences. Hepatitis A is usually transmitted when tiny amounts of stool from an infected person contaminate food, water, or surfaces. It typically causes an acute illness that can lead to fever, fatigue, nausea, and jaundice. There is no chronic form of hepatitis A, but severe infections can result in hospitalization and, in rare cases, liver failure and death.

Hepatitis B spreads through blood and certain body fluids. People can be infected during birth, through sexual contact, by sharing injection equipment, or through unsafe medical or cosmetic procedures. When infection occurs in infancy or early childhood, up to 90 percent of cases become chronic, greatly increasing the risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer later in life.

Vaccination has transformed the outlook for both viruses. Hepatitis A vaccines have been licensed since the mid-1990s and are now recommended for all children, as well as adults at higher risk, including travelers to countries where the virus is common, men who have sex with men, people who use drugs, and people experiencing homelessness or living with chronic liver disease. CDC and its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) added homelessness as an indication for hepatitis A vaccination after large outbreaks highlighted how quickly the virus can spread in shelters and encampments.

For hepatitis B, decades of data show that the vaccine is safe, highly effective, and capable of preventing most infections when the full series is completed. ACIP now recommends universal hepatitis B vaccination for all adults ages 19 to 59, as well as for adults 60 and older who have risk factors such as diabetes, dialysis, or other conditions that increase the chance of blood exposure. Adults 60 and older without known risk factors may also receive the vaccine. This universal adult approach was designed to reduce missed opportunities for vaccination, especially for people who may not be asked about or feel comfortable disclosing risk factors. In earlier remarks about the vaccine’s impact, Dr. José Romero, former director of CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, described the hepatitis B shot as “a powerful tool that can eliminate a disease that has caused generations of preventable illness.”

Hepatitis specialists note that the science behind these vaccines has remained stable even as federal vaccine policy has come under new scrutiny. In December, a federal advisory panel voted to remove the long-standing recommendation that all newborns receive a hepatitis B dose at birth, a change that has drawn strong criticism from major medical organizations who warn that weakening the birth-dose standard could lead to more infants slipping through the cracks. Experts say that, regardless of how those policy debates play out, getting children and adults vaccinated on time remains one of the most effective tools for preventing future infections.

Gaps in access and the push for health equity

Even as vaccines have become more widely available, many adults remain unprotected. Studies have found that AAPI communities, immigrants from countries with higher hepatitis B prevalence, and people who inject drugs are often under-screened and under-vaccinated, despite carrying the highest burden of disease. In many Black, Latino, and Native communities, lack of insurance coverage, difficulty taking time off work, and limited access to culturally and linguistically appropriate care all contribute to missed vaccinations and delayed diagnosis.

Federal officials argue that closing these gaps is essential to meeting national hepatitis elimination goals. The Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for 2021–2025, led by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, sets targets for reducing new infections and deaths and calls for expanded vaccination, testing, and treatment in communities that bear the greatest burden of disease. “Hepatitis is one of the diseases that has been deemed feasible and worthy of elimination,” said Dr. John Ward, director of the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination, noting that effective tools already exist but have not reached everyone who needs them.

Insurance coverage has improved in recent years. Under the Affordable Care Act, most new health plans are required to cover recommended preventive services – including hepatitis A and B vaccination and hepatitis B and C testing – without patient cost-sharing when delivered by in-network providers. Yet people who are uninsured, underinsured, or who receive care in overcrowded safety-net settings may still struggle to access vaccines, especially if clinics lack staff, stable vaccine supply, or funding to support outreach. In some states, federal Section 317 vaccine funds can be used to provide hepatitis vaccines for adults at little or no cost, but access varies widely by geography and program capacity.

Local health departments and community organizations have tried to bridge these gaps by bringing vaccines directly to where people live and receive services. In cities hit hard by hepatitis A outbreaks, mobile vaccination teams have partnered with shelters, syringe services programs, and street outreach workers to offer on-site hepatitis A and B shots alongside other services. National guidance now emphasizes one-time hepatitis B and C testing, along with vaccination, for people experiencing homelessness – an approach designed to identify infections earlier and connect people to care.

Advocates say those strategies are especially important for communities of color and immigrant neighborhoods where trust has been eroded by decades of unequal treatment. Community health workers, faith-based leaders, and grassroots organizations have played a key role in translating hepatitis information, helping residents navigate insurance and clinic systems, and countering misinformation about vaccines.

As the United States moves toward its 2030 viral hepatitis elimination targets, experts agree that progress will depend on whether vaccination, testing, and treatment truly reach those at highest risk. The CDC continues to urge clinicians to review hepatitis A and B vaccination status during routine visits and to offer vaccines during the same appointment whenever possible. For families, adults with chronic conditions, and people in higher-risk settings, health officials stress that immunization is available, safe, and often free or low-cost. For communities that have long faced barriers to preventive care, expanding access to hepatitis A and B vaccines could be a turning point – one that not only prevents infections today but also protects future generations from liver disease and cancer.

Stay Informed. Stay Empowered.

Also Read: NEKC Kidney Health Equity: Recognition at ASN Kidney Week 2025