The question of whether a woman’s menstrual cycle changes athletic performance has moved from locker-room lore to a fast-growing area of sports science, as more athletes and teams use cycle tracking to plan training and manage symptoms. The biology is clear: estradiol and progesterone rise and fall in predictable patterns across a typical 21–35 day cycle, and those hormones interact with systems that matter in sport, from temperature control and blood flow to breathing and fuel use. What remains less clear is how big the average performance effects are, and for whom they meaningfully matter.

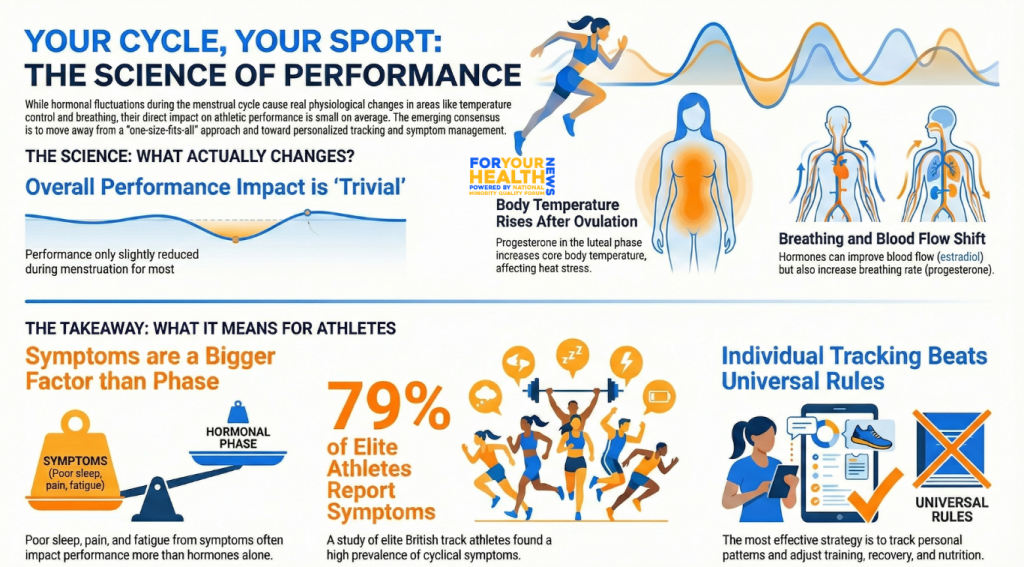

A major 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis in Sports Medicine, which pooled evidence from dozens of studies, found that performance differences across cycle phases tend to be small at the group level. Its conclusion was blunt: “exercise performance might be trivially reduced during the early follicular phase” (the days around menstruation) compared with other phases, but the evidence base was mostly low quality and too variable to justify one-size-fits-all rules.

That nuance matters for everyday athletes and elite competitors alike. The emerging consensus is that hormonal shifts can create real, repeatable patterns in thermoregulation, metabolism, neuromuscular function, and mood, yet the size and direction of those shifts can differ widely by person, sport, training status, and symptom burden. In practice, the menstrual cycle often matters most when it worsens sleep, pain, gastrointestinal issues, or fatigue, rather than because it predictably boosts or suppresses performance for everyone.

What hormones change—and what that can mean for performance

Researchers typically divide the menstrual cycle into the follicular phase (starting with bleeding) and the luteal phase (after ovulation), but the most meaningful physiological contrast is often between low-hormone days early in the cycle and the progesterone-dominant window later on. In the early follicular phase, both estradiol and progesterone are relatively low; in the late follicular phase, estradiol rises and peaks near ovulation; and in the mid-luteal phase, progesterone is high, with estradiol also elevated.

One of the most consistent findings is thermoregulation. Progesterone shifts the body’s temperature “set point” upward, meaning core temperature is typically higher in the luteal phase than in early follicular days. In a 2025 study in the Journal of Thermal Biology, researchers reported that core temperature remained higher during mid-luteal testing than early follicular testing during prolonged exercise in a hot chamber, even when perceived heat and effort were similar between phases. As per ScienceDirect, the paper notes prior evidence suggesting a roughly 0.18–0.56°C higher core temperature in the luteal phase compared with early follicular days, a change that can be small on paper but meaningful in sports where heat stress, dehydration risk, or recovery are limiting factors.

Cardiovascular dynamics and breathing can also shift. Estradiol has long been linked to vasodilation through nitric oxide–related pathways, which is one reason late follicular phases are often hypothesized to support endurance and cooling through improved blood flow. At the same time, progesterone is associated with increased ventilatory drive. A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis on ventilation across the menstrual cycle reported higher minute ventilation in the luteal phase than the follicular phase at rest and during submaximal exercise, and found that progesterone changes helped predict those ventilation changes during submaximal work. For some athletes, that could translate into feeling more “winded” at a given pace, especially when combined with heat or poor sleep.

Energy metabolism is another area where menstrual-cycle physiology and performance intersect, though findings are mixed. Reviews of substrate use suggest that hormone fluctuations can influence carbohydrate and fat oxidation, glycogen storage, and appetite-related signals, with progesterone-dominant phases often discussed as periods where some athletes experience more cravings, perceived fatigue, or a different “fuel feel” during training. In the real world, these metabolic shifts can be hard to separate from the more immediate effects of symptoms such as cramps, headaches, bloating, or gastrointestinal upset.

Those symptoms are common in athletic populations. A 2023 Sports Medicine systematic review on menstrual-cycle disorders and symptoms in athletes, covering 6,380 athletes, reported pooled dysmenorrhea prevalence of about 32% (with a wide range across studies) and noted that most evidence relies on retrospective self-report. In elite settings, the burden can be even more visible: a Frontiers study of elite British track and field athletes reported that 79% experienced at least one cyclical symptom, and many athletes described wanting better tools and support to manage symptoms around competition. A broader 2024 scoping review found extreme variation in how many athletes reported their performance being negatively affected by their cycle, with symptoms frequently cited as the main reason.

The contraceptive question adds another layer. Oral contraceptives blunt natural hormone peaks and create “pseudo-phases,” which has led some athletes to use them for symptom control or to reduce cycle uncertainty around key events. But when researchers have compared oral contraceptive users with naturally menstruating women, the average performance differences again appear small. A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded: “OCP use might result in slightly inferior exercise performance on average… although any group-level effect is most likely to be trivial,” and found performance was generally consistent across the pill cycle itself. The authors emphasized individualized decision-making, particularly because contraceptives are used for many medical and personal reasons beyond sport.

A newer wave of studies is also challenging simplistic “follicular good, luteal bad” narratives. For example, a randomized crossover trial published January 7, 2026 found no meaningful differences in aerobic performance or cardiac autonomic responses between early follicular and mid-luteal phases in physically active women, though perceived exertion at a key intensity threshold differed by phase. Findings like these help explain why elite practitioners increasingly treat cycle phase as one input among many, not a rigid performance forecast.

For athletes, coaches, and clinicians, the most actionable takeaway is to track patterns and plan around the individual, especially when symptoms are strong. That may mean scheduling the hardest sessions when an athlete historically feels best, building in extra attention to sleep and recovery during symptom-heavy windows, and preparing for heat exposure during luteal-phase training and competition. Nutrition can matter too, not because there is a universally “correct” phase-based diet, but because symptoms and menstrual blood loss can change what an athlete needs. In guidance for supporting female athletes, the American College of Sports Medicine notes that “up to 35% of female athletes” may experience iron deficiency, emphasizing the importance of monitoring iron status and consistent intake of iron-rich foods, particularly for athletes with heavy bleeding.

Health equity makes this conversation even more urgent. Menstrual disorders and uterine conditions that cause heavy bleeding are not evenly distributed, and the downstream impacts—fatigue, anemia, pain, missed training, delayed diagnosis—can be shaped by barriers to care. Reviews have reported that fibroids are common overall and are more prevalent among Black women, with estimates of very high cumulative incidence by midlife. When a sport system treats menstrual health as private, shameful, or “not performance-related,” athletes who already face structural inequities—including many women of color navigating gaps in culturally competent care—can be left to manage debilitating symptoms alone.

Researchers are increasingly explicit that the science itself needs to catch up. An International Olympic Committee–linked supplement in the British Journal of Sports Medicine noted that major sports injury and illness surveillance recommendations historically included “little, if any, focus on female athletes,” and called for better data capture across female athlete health domains. Until studies routinely validate hormone status, recruit larger and more diverse samples, and include more elite athletes across a range of sports, the best-supported approach will remain personalized: treat the menstrual cycle as a real physiological factor, but one that should guide curiosity and planning rather than impose limits.

In women’s sports, the shift now is less about asking whether the menstrual cycle “helps or hurts,” and more about building environments where athletes can name what they feel, get evidence-based medical support, and train with their biology rather than around it. As participation grows and performance margins shrink, especially at the elite level, the next frontier is not a universal cycle formula, but better research and better care—designed for the full diversity of women’s bodies and lives.

Also Read: U.S. Vaccine Schedule Changes Under RFK Jr. Raise Concerns for Communities of Color